The world's population is growing. At the same time, an ever-increasing proportion of people are being drawn to the cities. The consequence is an increase in density which means, particularly in the cities, upwards. Simply put, the cities with the greatest population density need skyscrapers to meet the increasing demand for residential and working space. Such skyscrapers usually have a well-known look: more or less linear and, of course, tall, narrow bars. This form can be found over the world and is likely to make up more than 99 percent of all high-rise giants. However, there are also architects who are specifically designing new types of super high and super-dense buildings.

The reason that the cuboid or quasi rectangular block is the most widespread form of skyscrapers is very simple reason: it is the most predictable. Thanks to modern computer technology, times in which such simple forms were needed are long past because the structural analysis had to be done by hand. So why not help the cities, which do not necessarily become more beautiful by increasing their density, to construct buildings which make the density appear a little more interesting or, maybe even, a better place to live? For instance, by integrating more "nature".

Like a picture: MAD’s Shan Shui architecture

No region of the world is so impacted by increasing urbanization and density as Eastern and Southeast Asia. So it's no surprise that the most skyscrapers are generated there - as are new concepts to improve them. A pioneer in new approaches to handling high density is Ma Yansong. The founder of the Beijing architectural firm of MAD Architects wanted to create a new type of high-rise buildings which gives greater attention to the environment. This does not mean primarily a building with a good eco-balance. It involves buildings which recreate natural conditions and blur the boundaries between urban and natural landscape. Ma Yansong calls this “Shan Shui architecture”.

Shan Shui is a term from traditional Chinese landscape painting which literally means "Mountain water”- both of which are central elements in this form of painting. Now MAD has translated this art form into architecture. What emerges are building forms that are very similar to the traditional representation of mountain landscapes. And water, as in the paintings, is also of central importance. For example, staged in the form of artificial waterfalls and ponds. An extensive amount of plants also contribute to the "naturalization" of this architecture.

Chaoyang Park Plaza in Beijing, which was completed in 2017, is an example of this type of architecture . Two huge towers (the highest is 120 meters) stand out in the office complex which consists of ten buildings clearly modeled after the soft curved mountains of a Shan Shui painting. However, with their sandwich-like offset levels, the smaller office buildings are more reminiscent of layered stone slabss. The impression of an architecture which derives from nature is wonderfully illustrated in the images of the architectural photographer, Iwan Baan. The towers appear almost poetic through the Beijing smog, like mountains in the mist.

Green pyramids in Manhattan: BIG’s “Courtscraper" via 57 West

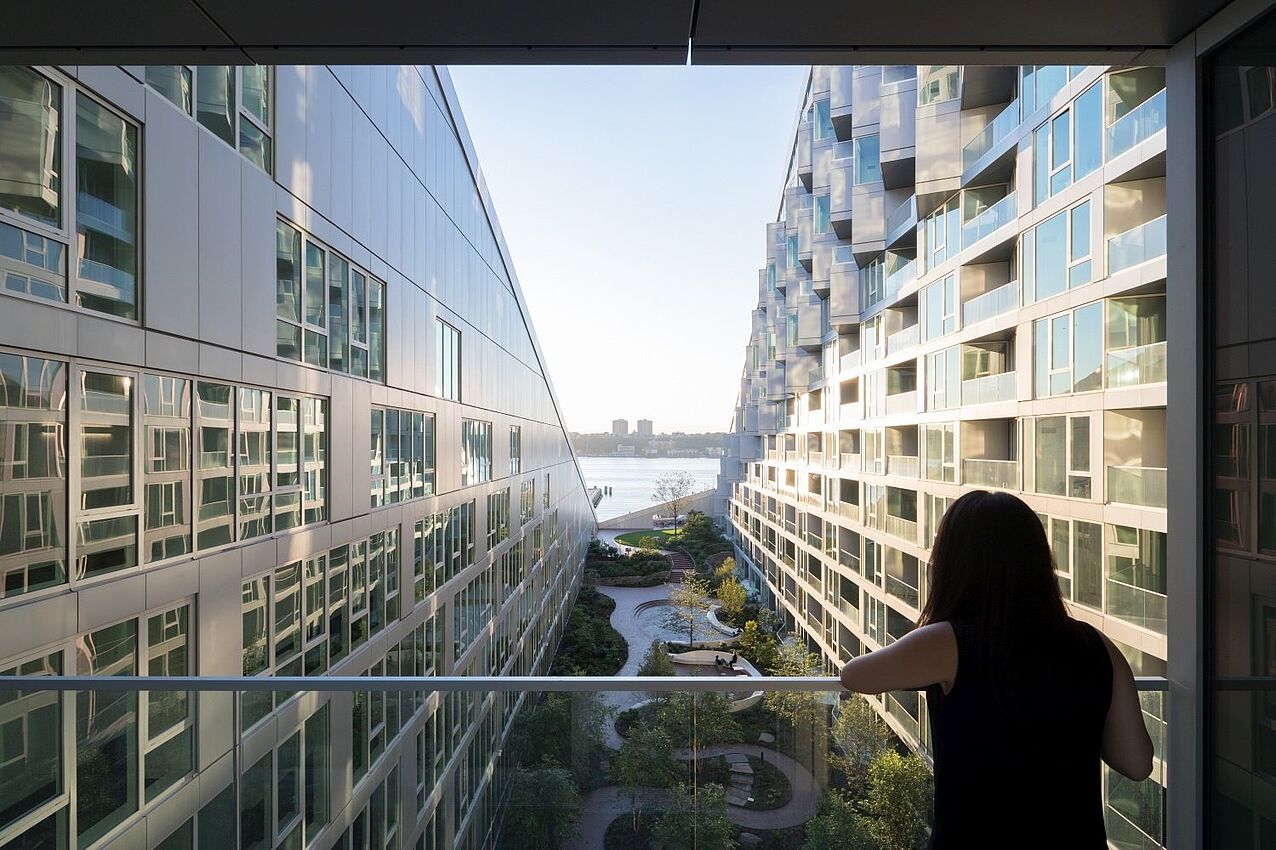

New solutions for high density are being developed elsewhere as well. One award winning new project is located in New York: VIA 57 west from BIG. With this building, which was completed in 2016, the Bjarke Ingels Group also created an entirely new type of high-rise building by combining two established building forms. VIA 57 West is a combination of typical New York skyscraper and a European outer-city apartment development. In English: a "courtscraper".

When combined, both types result in an extremely steep, 142 meters high, crooked pyramid which opens toward the center and encloses a park-like courtyard. The latter curiously has the same proportions as Copenhagen’s Olmsted Park - only 13,000 times smaller. This mini park forms not only the formal but also the conceptual heart of the project. For BIG it was a question of weaving some greenery in a post-industrial manner into the “urban fabric" of Manhattan.

Conclusion

Both types are similar to each other in their attempt to integrate "nature" in the architecture, but have developed completely independent stylistic idioms. VIA 57 West received both the International Highrise Award and the CTBUH Skyscraper Award for its idea. While the New York project re-combines long-existing elements, it also represents a return to the Shan Shui type of design. Ma Yansong regards it as an approach to traditional Chinese architecture which attempts to be in harmony with nature and whose buildings blend unobtrusively into the landscape by means of an extremely horizontal form of construction. Since the latter is impossible in high density areas, a replica of a natural topography might still be the best solution in this case.