Carbon concrete: building material of the future for sustainable construction

Until a few years ago, the lighting of cities was technically limited both in its design and in its extent. However, this has changed fundamentally in many places due to the introduction of LEDs. Despite their low power consumption, light-emitting diodes offer high light quality and extremely diverse and differentiated lighting options. Many cities are now taking advantage of these properties to stage themselves, promoting a culture that allows city life to penetrate deeper into the night. But where there is a lot of light, there is also shadow: This displacement of the night also poses a threat to the climate and the ecosystem.

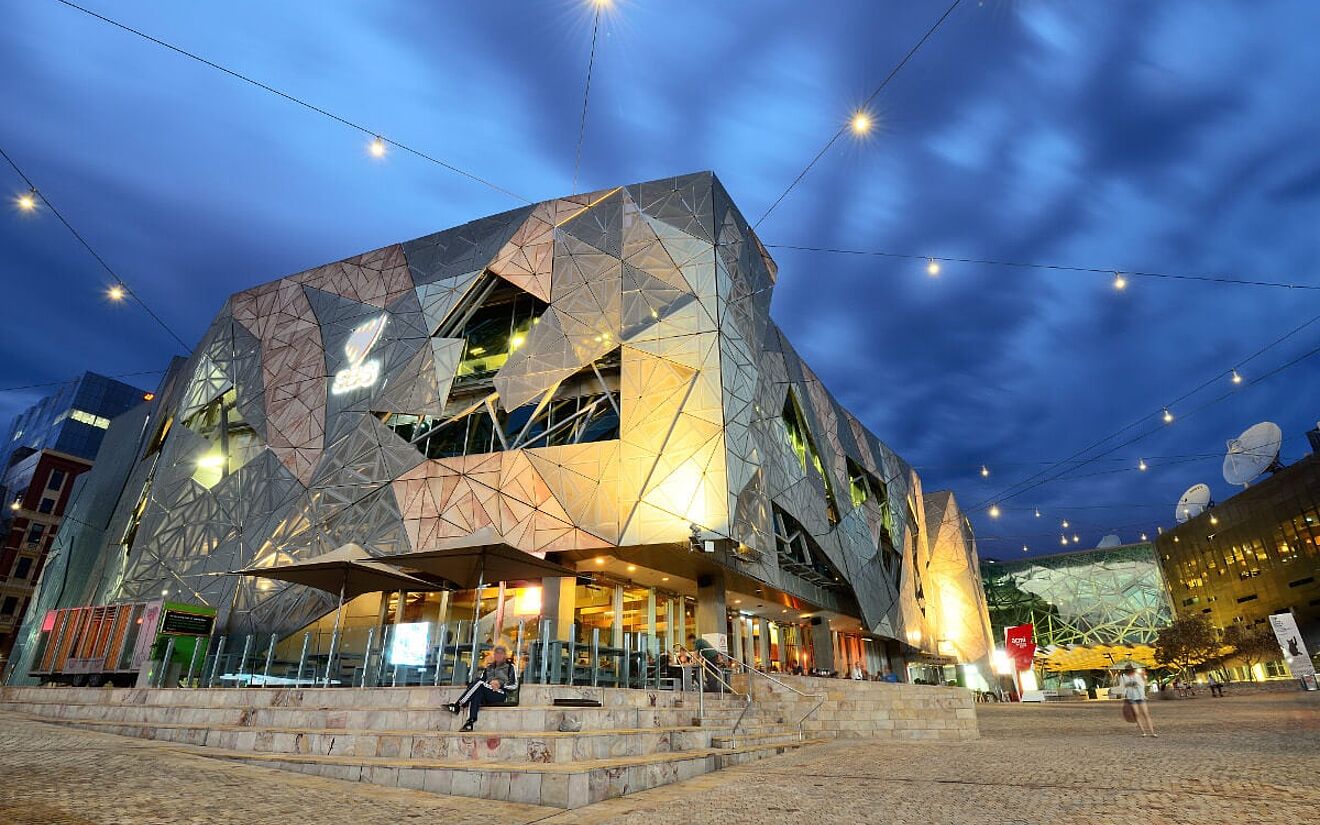

It is a bit like with the hen and the egg. Life in the cities is increasingly concentrated on public spaces such as cafés, pubs, etc. and expands deeper into the night. The latter development goes hand in hand with a technological one. LED lamps not only allow improvements in classic city lighting, i.e. street lighting, but also offer the possibility of selectively setting certain objects and zones in scene in a wide variety of luminous intensities and colours. Thanks to LED technology, even at night it is possible to create places with a very high quality of life that previously remained in the dark.

"Lightscapes" instead of deserted squares

LEDs therefore help to make night-time cities more attractive. This could have far-reaching consequences in several respects. The multinational engineering firm ARUP sees this as an opportunity to create "lightscapes" instead of just the traditional illuminated traffic routes, which invite people to linger and serve better interpersonal interaction. One example is Leicester Square Garden in London. Popular and much frequented during the day, the public square was avoided at night until it was transformed into an attractive "lightscape" in 2012 with a new lighting concept. Since then, the place has also been popular with night owls.

Revolutionary city lighting until 2053

However, ARUP's vision for an "enlightening" transformation of cities goes much further. In an animated video, the engineering office shows what the future could look like until 2053. Here, intelligent and comprehensive urban lighting meets the needs of a 24-hour economy and enables a society that practically never has to walk through darkness. At first it sounds like permanent lighting, but it is precisely this that should be avoided by connecting everything via the Internet of Things and using light practically only where it is actually needed.

The shadow side of light

Such an intelligent, demand-oriented use of light is already necessary for two reasons. The first is energy consumption and the associated CO2 emissions. Although the economical and versatile LED lamps make extensive differentiated lighting possible in the first place, they also represent a classic rebound effect. So there is a danger that more energy will ultimately be consumed, not in spite of, but because of, economical technology.

The second reason lies in the worrying effects on the environment caused by too bright nights. More than a tenth of the earth is already illuminated at night. If the brightening of the night sky is added, the figure is as high as 23 percent - and rising. However, the vast majority of all species, from whales to plankton and from sequoia to daisies, have adjusted in their evolution to brightness during the day and darkness at night. Night lighting therefore disturbs the mating, reproductive and migration behaviour of animals as well as the development of plants.

Red light as a solution?

Ultimately, even direct effects on only certain species lead to serious changes in the entire ecosystem. White light has the most serious effect on the environment, as a study¹ by Dutch scientists has shown. Red light, on the other hand, seems to be much more harmless - a finding that is already finding its way into Dutch urban planning. Whether red light can also offer the high quality of living of sophisticated outdoor lighting concepts such as those in Leicester Square, however, is doubtful.

¹ royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2017.0075